Christian Nationalism: A Primer (II)

What Christian Nationalists Want: A Christian Polis

In the last post, I briefly introduced Christian nationalism, outlining key concepts and my research subjects. In this post, I intend to briefly explore the political aims of Christian nationalism. But first, a quick word on methodology.

How I Did This

Unlike other studies, which rely on nationally representative surveys, I took a content-focused approach, tracking and studying what RCN proponents said. I used three sources for my research: books, podcasts, and posts on X (Twitter).

First, the books. Stephen Wolfe’s book, The Case for Christian Nationalism, is probably the most comprehensive articulation of an RCN vision. You can read a high-level summary here. I would argue that it’s a foundational text, insofar as RCN ideology goes. I also read through Andrew Isker and Andrew Torba’s Christian Nationalism: A Biblical Guide For Taking Dominion And Discipling Nations. Far shorter, and far less intellectually satisfying, it’s also less helpful. But Torba and Isker are key voices in this movement.

Second, social media accounts. I spent several months collecting posts from RCN proponents. They have a vibrant presence on X (Twitter)—I’d classify them as Very Online. I limited my analysis to users who explicitly identify with the Christian nationalist label—or speak sufficiently favorably about it to suggest strong sympathy with the movement—have over 1,000 followers, and fall within the orbit of the generally Reformed Christian theological camp. I collected around 450 posts from 23 accounts that fit this criteria. Some of these accounts were smaller, others were quite large (the median was something around 36,000 followers).1

Third, podcasts. I also examined several episodes from three different podcasts. Now, to be clear, I didn’t listen to these episodes (I’m not really a podcast person to begin with, and let’s be honest, these guys are hard to listen to). Instead, I used digital transcription software to convert them to text, and then coded selected episodes. When I found something particularly…odd, I’d confirm that the transcription was correct by checking out the audio. I listened to Stephen Wolfe’s podcast “The Lone Bulwark, Andrew Isker and C. Jay Engel’s “Contra Mundum,” and the podcast by Joel Webbon, Michael Belch, and and Wesley Todd’s “Right Response Ministries.”

I offer this boring prelude to help make a bit more sense of the citations I offer as support for my claims.

The Christian Nation

Reformed Christian Nationalists want a Christian nation. That much is clear. But it’s more than just wanting lots of people to be Christians (i.e., mass conversion), or passing legislation that is ethically aligned with Christianity. They want a nation that is formally aligned with and which promotes Christianity.

1. A Christian State, a Christian Church

Like countless other Christians, RCNs believe that human government is an institution ordained by God to restrain evil. They also believe that the government is ordained to promote human flourishing. What makes them unique, however, is this logic:

civil government should seek to procure human flourishing;

the highest human flourishing occurs when it is rightly ordered to God;

civil government should seek to fulfill that flourishing by directing people to God;

since God can only be known via true religion, and Christianity is the true religion, then civil governments ought to direct its people to God, via Christianity (see Wolfe 2022:183).

(Now, let’s be clear here. I am sympathetic to their theological claims—namely that I believe Christianity is the highest human good, and that it is the true religion. I’m a pastor and a Christian, and I wish everyone knew Jesus! In my analysis, I am not critiquing the fundamental claims of Christianity. Rather, as should become clear, my critique is on the political application of Christianity.)

Since Reformed Christian Nationalists believe that Christianity is the highest good that humankind may pursue, they argue that religious life should be integrated into political and social life. As a result, they explicitly reject the assumptions of political liberalism, believing that Christianity must inform the civic life, laws, and social fabric of a nation. Wolfe states this plainly:

“If the father, who rules over the natural family, can know and act on supernatural knowledge as father—ordering his household to Christ—then so too can the magistrate know and act on supernatural knowledge as magistrate and thereby order civil society to Christ” (Wolfe 2022:368).

However, this doesn’t mean they believe the church should run the state. They’re not direct theocrats. In fact, RCNs believe that civil government and the church ought to be kept separate—while operating in a complementary relationship. For example, Wolfe writes,

“No civil magistrate can command or exercise dominion over the conscience. Civil power cannot legislate or coerce people into belief; it can only command outward things—to outwardly do this or not do that” (Wolfe 2022:182).

The Statement on Christian Nationalism and the Gospel likewise affirms such a distinction: “WE AFFIRM that the Church and the state each possess their own sphere of influence. For example, church officials ought not to write or enforce civil laws in their capacity as church officials, and civil officials ought not to administer church ordinances or dictate doctrine…” (see also Torba and Isker 2022:106).

The logic for this seems, more than anything, to be rather pragmatic. For example, C. Jay Engel explains:2

William Wolfe agrees, writing that the “spiritual transformation in the life of an *individual* won’t magically solve the problems of ‘late modernity.’ Only political solutions, grounded in Christian truth, or natural law if you prefer, will do that.”3

So while Reformed Christian Nationalists believe that the state should be explicitly aligned with Christianity, its proponents frequently imagine solutions which are far more, shall we say, worldly than those which might be offered by pastors or Christian theologians.

2. A Government Which Promotes Christianity

So what would policy and society look like under a Christian government, imagined by the RCNs? While there’s no Project 2025 policy book for RCNs, they do regularly point to several features of civic life they would change. At a high level, it seems to involve promoting and enforcing a public morality grounded in Christianity. Of course, the particulars are where things get really interesting. So let’s look at a few themes.

A. (In)Tolerance of Other Beliefs

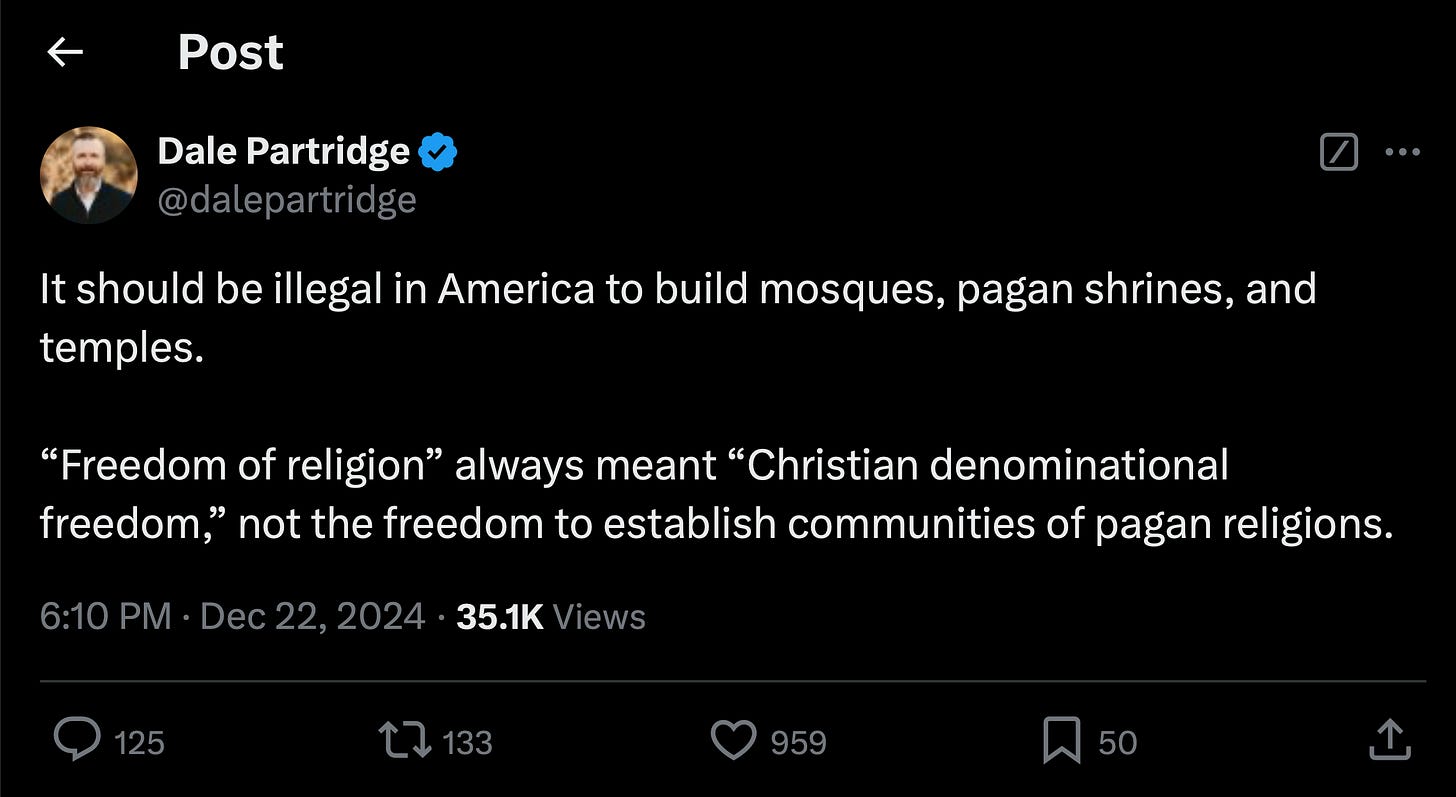

Wolfe argues that civil government may suppress other religions, arguing that, a) government should restrain that which can harm others; b) false religions can cause harm to others; therefore, c) false religion can be restrained (Wolfe 2022:361). Wolfe does not advocate for an idealogical totalitarianism, allowing for viewpoint diversity—within Christian orthodoxy. In other words, as long as said diversity exists within the boundaries of orthodox Christianity and orthodox Christian ethics, it can be tolerated; otherwise it is excluded (Wolfe 2022:384). Others have been more blunt:4

B. Christian Civil Law

Reformed Christian Nationalists believe that Christianity has the best tools necessary for shaping civil law. After all, laws encode morality. Stephen Wolfe defines civil law as “an ordering of reason, enacted and promulgated by a legitimate civil authority, that commands public action for the common good of civil communities” (Wolfe 2022:248). However, he is clear that it is limited to those spheres which cannot be otherwise regulated “Thus, the individual, family, society, civil associations, and churches have primacy in ordering the things of life” (Wolfe 2022:250).

Aside from this caveat, RCNs offer a series of broad recommendations. Stephen Wolfe, for examples suggests that a Christian government would stand behind “the funding of church construction; ministerial and seminary financial support; the suppression of public blasphemy, heresy, and impious profanation; obligating Sabbath observance; and other things.” (Wolfe 2022:182)

In the Statement on Christian Nationalism and the Gospel, the authors affirm that a Christian government would promote “national recognition of Christian essential orthodoxy,” the establishment of the “second table of the Ten Commandments (laws five through ten) as the foundational law of the nations,” with additional warnings against blasphemy against “the One, True, and Living God.”5

Additionally, RCNs clearly favor law enforced with harsh, and even violent, penalties for lawbreakers. Stephen Wolfe, in a podcast, invoked the social power used in contemporary society against those who say or do racist things, and argued that Christians should use their social power to do the same to atheists.6

But it goes beyond social power. If state sanctioned violence is Christianized, what would the result be? We get a glimpse by the way RCNs talk about crime. Quote-posting a New York Post article about a gay couple who sexually abused their adopted sons, AD Robles posted, “One day Christian Nationalists will make the death penalty great again,” and he additionally reposted Ben Zeisloft who wrote “We need to bring back public executions,” with a photo of a noose, and the text, “After a fair trial of course.” Other examples include Auron MacIntyre, who posted a meme of Anakin Skywalker with the words, “I would also like to abolish mass incarceration,” and explained: “But seriously long term incarceration is much worse than corporal punishment. Fine people, cane people, execute the worst offenders. No one is helped by a 10 year prison stays at taxpayer expense.” And Josh Daws demanded:7

Reformed Christian Nationalists appear to believe that the state should implement stringent bodily punishment as a just consequence for lawbreaking, though how precisely this would be applied, and whether such violence would be acceptable to all RCNs, is not entirely clear.

C. Led By a Strongman

If you’re tracking along this far, you’re probably wondering, “How in the world do they think they’re going to accomplish this in these United States of America in the year of our Lord, Twenty Twenty Five? RCNs acknowledge the problem. Their solution is not an enthusiastic hearts-and-minds campaign, however, but a direct seizure of power, to implement this vision through sheer force of charismatic will.

We’ll come back to this in a future post, because their vision of the so-called “Christian prince” is deeply anti-democratic, weird, and warrants more space than I should give here. But I’ll give you a quick glance with another Wolfe quote:

“I cannot conceive of a true renewal of Christian commonwealths without great men leading their people to it. Nor can we expect the national will to find its end through an administration led by wonks and regulators. So I will primarily use ‘prince’ as the mediator of the nation’s will for itself. This title denotes both an executive power (viz., one who administers the laws) and personal eminence in relation to the people” (Wolfe 2022:278-279).

He goes on to describe this arrangement as a “measured and theocratic Caesarism” (Wolfe 2022:279), and the prince as a “sort of national god, not in the sense of being divine himself…but as the mediator of divine rule for this nation and as one with divinely granted power to direct them in their national completeness” (Wolfe 2022:287-288).

D. Reclaiming a Heritage

Reformed Christian Nationalists tether this vision of a religiously integrated society to an imagined heritage. That is, they operate under the assumption that the United States was formed as a Christian nation, and that we would do best to return, in some form to that context. For example, Stephen Wolfe offers a nuanced argument that the assumption of the founders was always that religion—and Christianity in particular—was necessary for a healthy, functioning republic. Furthermore, he argues that the existence of the Establishment clause was a peculiarity of the majority Ango-Protestant composition of the new nation, and reflected concerns about intra-denominational concerns:

“Among the founders, all believed that a religious people were necessary for civic morals, public happiness, and effective government, and most (if not all) thought that Christianity provided something distinctive in this regard. Most believed that government had a role in promoting, supporting, and protecting true religion, even particular denominations, though not at the expense of full toleration. Most believed that violators of natural religion could be censored and that religious expressions that “disturb the Peace, the Happiness, or Safety of Society” (as Mason wrote) could be suppressed. And most founders explicitly grounded their principles of religious liberty in Protestant principles….” (Wolfe 2022:43; cf. Torba and Isker 2022:134)

While Wolfe is explicit that he has no interest in attempting to recreate an 18th century cultural context, he does want a kind of retrieval where Christianity is viewed as a cultural and political asset—a small “r” republican virtue of sorts—rather than an obstacle for civic life.

RCNs, however, take another step. While they don’t necessarily want to return to colonial America, they do desire to return to a particular cultural and demographic point in time. Wolfe again: “the whole tradition—between the early settlements to the early American republic—is an American, ethno-cultural inheritance that must be reclaimed and serve as an animating element of American Christian nationalism and a resource for American renewal” (Wolfe 2022:432).

“Ethno-cultural” carries a lot of freight here. What does he mean, exactly? And what has that to do with a religious society? The short answer is that RCNs believe that ethnicity and nation are effectively synonymous, and a nation should seek ethnic solidarity, or even homogeneity. But this needs to be unpacked further—in our next post.

—Till then.

The primary accounts I cited used the following handles, for the curious: @BasedTorba, @AuronMacIntyre, @dalepartridge, @smashbaals, @William_E_Wolfe, @Brian_Sauvé, @BonifaceOption, @Eric_Conn, @perfinjust, @BenZeisloft, @JoshDaws, @contramordor, @jchasedavis, @jonharris1989, @ADRoblesMedia, @Wesley_Todd_.

C.Jay Engel (@contramordor), X (Twitter), accessed 01/09/2025, x.com/contramordor/status/1877359497754059010

William Wolfe (@William_E_Wolfe), X (Twitter), accessed 01/08/2025, x.com/William_E_Wolfe/status/1877051942997770445

Dale Partridge (@dalepartridge), X (Twitter), accessed 12/23/2024, https://x.com/dalepartridge/status/1870985338195423603

https://www.statementonchristiannationalism.com/

Gordon, Chris. 2024. “Wolfe vs. Gordon: A Critical Conversation On Christian Nationalism.” Abounding in Grace Podcast. Retrieved June 20, 2025.

Josh Daws (@JoshDaws), X (Twitter), accessed June 21, 2025, https://x.com/JoshDaws/status/1918346041985847483

I appreciate you drawing from Twitter/X and other social media platforms. One of the ways that Christian Nationalists have been able to evade serious notice from academics (whether intentionally or not, I don't know), is by building a Very Online community. Most academics tend to feel like social media content is beneath their notice - I don't think we live in that world anymore.

Love this!