The Case for Casting a Losing Vote (Part Three)

The Nasty Problem of Picking an Evil

This is a short series on why I believe a third party vote is not just a reasonable option, but a strategic one. On Thursday, I introduced the problem of voting in a duopoly; yesterday I considered the nature of what a vote is.

Today, we’re considering a core problem in so many of the discussions around voting: the nasty problem of picking a particular evil.

An Entirely Practical Choice

Many arguments for voting boil down to a simple commitment: we must choose the lesser of two evils. You’re no doubt familiar with the logic. Neither side is great, but there are only two options, and so at the end of the day, you have to be practical darnit, and strategically choose the option that’ll do the least amount of harm.

It makes sense, at a intuitive level. After all, if we really only have two options, then it comes down to an almost mathematical simplicity. Figure out which option is the least problematic and run toward that one.

But from where I sit, this argument doesn’t survive the pressure of scrutiny. Let’s unpack why.

Deconstructing a Lesser-Than Logic

Bear with me while I propositionally dissect this reasoning and lay it out part, by part, as it pertains to voting.

Both options are bad. The first assumption in the lesser-of-two-evils logic is that, well, there are two evils. Neither party is ideal. Both parties, platforms, and politicians are flawed, even detrimental. But alas, we’re realists; we must face the music.

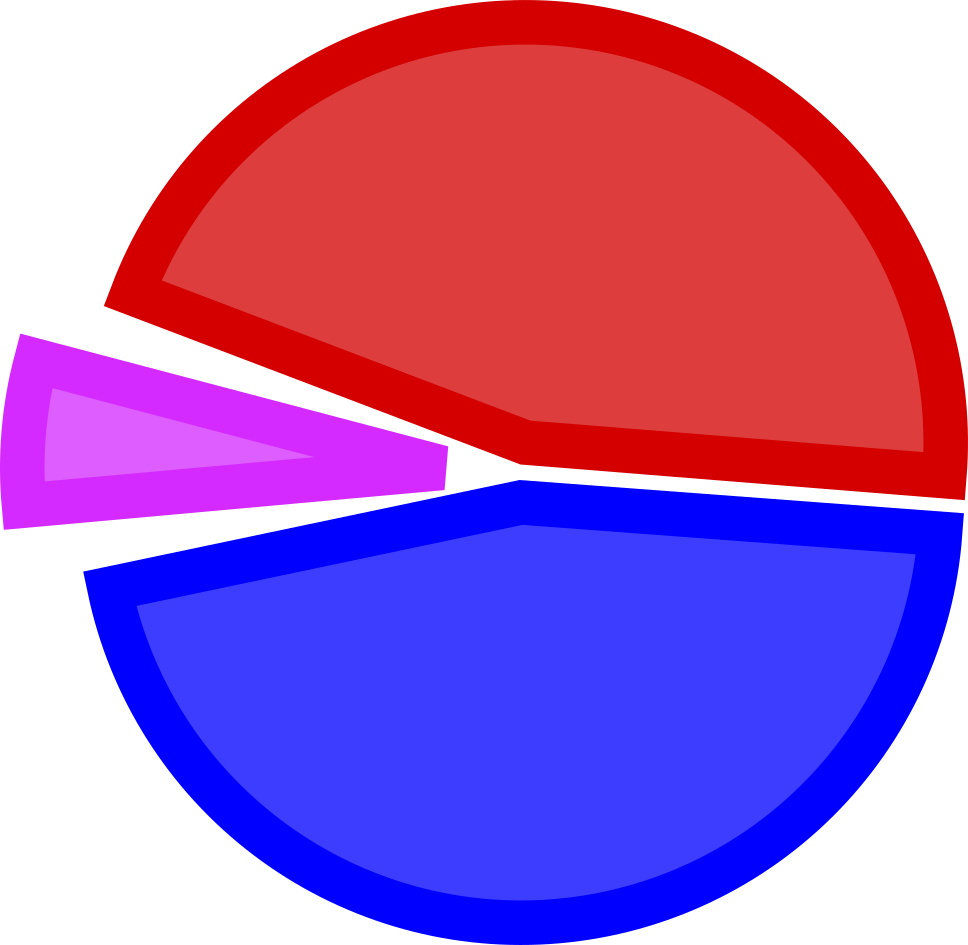

There are only two options. The next assumption is that it our choice is binary. In the American electoral system, there are functionally two parties. Sure, other parties exist, but none ever gain sufficient representation to make a difference. Statistically speaking, in November, we will either elect a Republican, or a Democrat as President of the United States. (This is less the case for other, less prominent offices.)

Because there are only two bad options, and one of those two options will be elected, we must determine which of those two bad options is the less bad. At the end of the day, because we have nothing but bad choices, we’re reduced to running damage control, rather than investing in a constructive politic. But once again, we’re realists.

It makes sense. It’s practical. It’s one way to handle the difficult situation we all face. But the more I consider this logic, the more I believe it’s deeply problematic for a Christian.

Three Problems

First, and most pragmatically, it’s simply not true that there are only two options.

Statistically speaking, we’ll end up with a Red or Blue candidate. But there is no prescription that it must be so. Let me repeat that: it doesn’t have to be this way. Because we operate in a democratic republic, if 49% of voters voted for, say, the American Solidarity Party candidate, guess what? The problem is that we’ve been told that any vote that’s not one of the two Big Ones are wasted votes, are meaningless, and will never make any difference. There are obviously vast hurdles to overcome to make a third party vote politically viable, but the point that I want to make clear is that we don’t actually have our hands tied at a formal or structural level.

Second, realistically, how does one choose between evils—especially when the scale is finely balanced?

Because we all will evaluate the relative vileness of each candidate differently, we’ll each end up with a differently weighted scale. But, at least in this election, I would argue that the weight of evil is finely balanced between a morally repugnant actor (and morally ambiguous platform) on the one hand, and a platform that actively advocates injustice.

How does one make such a judgment? The difference is far too narrow, from a pragmatic perspective. If we elect one candidate, we get a whole set of problems and liabilities. If we elect another, we get another set of problems and liabilities.

Beyond this, what metric are we actually using to evaluate the lesser of evils? Are we considering only how it will affect us? Or are we also considering how it will affect the vulnerable? The poor? Our enemies? Are we considering how their policies and character will hold up next to the light of God’s righteousness? The calculus is enormously complex, and frequently extremely subjective. Which means we must exercise great caution.

Third, and perhaps more pressing than the last point: in choosing between evils, we are still choosing an evil.

“Yes Bob, but we live in a fallen world. You’ll never get Jesus as your president.” Fair. But as a follower of Jesus, my ethic was never, and must never be tied to a utilitarian calculus. I follow Jesus and his way in spite of the social, political, or cultural consequences. Regardless of whether it helps me to “win” or whether it costs me something fierce.

Right?

Right…?

Of course, my idealism is frustrating. I’ve always been an idealist, to some degree. In kindergarten, my teacher complained to my parents that I was far too black-and-white in my perspectives. I suppose I’ve never really grown out of that.

But then again, if gaining the world and losing our souls means anything; if denying ourselves and taking up our instrument of execution and following Jesus means anything; if believing with Peter that “we must obey God rather than man” (Acts 5:29)—then shouldn’t we seek to bring our vote into alignment with this costly ethic? Especially when the act of casting a private vote is one of the least costly actions we can take as citizens?

Toss It Out

My recommendation is that, as Christians, we ditch this logic wholesale and embrace an entirely different set of ethical considerations. That we stop thinking in utilitarian terms, and evaluate our options in a positive, constructive ethical frame that asks, “what does it mean to follow Jesus in this moment?”

This calls for thoughtful, difficult—and in this political climate, very creative solutions. But I think it’s worth it. Especially in light of our calling to prophetic witness. More on that next time.

—Till then.